Behind the Seen

50+ years of stewardship on Barton Creek

an essay by Daryl Slusher

When Austinites of today, or visitors, swim in Barton Springs or hike and swim along the Barton Creek Greenbelt, they are able to do so because of the vision, hard work, and determination of generations who came before them.

1950s

The Austin naturalist, Barton Springs swimmer, and writer Roy Bedichek helped set the tone about how much Austinites value Barton Creek and the natural environment. In a letter he wrote to a friend in the 1950s: “I will fight to the last ditch for Barton Creek, Boggy Creek, cedar-covered limestone hills, blazing star and bluebonnets, golden-cheeked warblers and black-capped vireos, and so on through a catalogue of the natural environment of Austin, Texas.”

The Golden-Cheeked Warbler

The rare Golden-cheeked Warbler was listed as endangered in 1990 due to habitat loss.

The Travis County Audubon Society was among the first groups to call for the preservation of Barton Creek.

Photo Credit: Austin History Center/Austin Public Library AR-Q-005-046

Bedichek may have been referring, at least in part, to the proposed development of Barton Hills, advertised in 1956 as Austin’s first air-conditioned suburb, located above the Creek, and just upstream of Barton Springs. Barton Hills prompted serious concern among the most Austin observant nature enthusiasts. In particular, Austin Parks Director Beverly Sheffield and members of the Audubon Society, were concerned that the development would threaten the flow of the Springs and endanger water quality. Sheffield called for the City to purchase nearby land to help protect the creek and springs. City leaders ultimately responded with a token, gesture—buying 29 acres nearby. It was small, but also significantly the first property purchased with the intention of protecting Barton Springs.

1970s

Other like-minded citizens including long-time Parks Board Chair, Roberta Crenshaw, with parks advocates Janet and Russell Fish stepped forward to advocate for open space and Austin’s natural environment. Crenshaw donated land from her personal estate in an effort to preserve public open space and the Fishes built Austin’s first hike-and-bike trail with their own funds along Shoal Creek. Together Crenshaw and the Fishes created Austin’s first home-grown environmental organization called the Austin Environmental Council in an effort to awaken an awareness of environmental concern, as the city itself was not invested in this effort.

Image from May 1970 special issue of the Austin Chamber of Commerce magazine

Founding members of the Austin Environmental Council, Engineer Russell Fish, internationally-known ecologist Dr. Frank Blair, Mrs. Fagan Dickson and Attorney Frank Booth.

The first visionary and bold effort to permanently protect the Barton Creek watershed came from Austinite Phil Sterzing, who came up with an ambitious plan to save the area after witnessing careless destruction along Barton Creek near Barton Springs. His plan for a Barton Creek Park captured the imagination of the public-at-large. An emerging confluence of thought among creek advocates was reflected in a 1970 petition published in the Austin American from the Citizens for Barton Creek Park. Signers of the petition called on the City Council to pass ordinances protecting all Austin creeks and to buy land and establish a Barton Creek Park from Barton Springs to Highway 71 where it crosses Barton Creek.

Photo courtesy: Austin American-Statesman

The Zilker Park Posse helmed by Betty Brown raised awareness about threats to Barton Creek in the late 1970s.

An April 1970 petition signed by hundreds of Austin citizens urged the City to purchase a Barton Creek park and lower building density in the areas near the Barton Creek canyon.

The efforts of these citizens to preserve the Creek and Springs brought advances and lasting change. The trail envisioned by the 1970 signers of the petition did not make it all the way to Highway 71. No, it was blocked by the sprawling Lost Creek subdivision. But the Barton Creek Greenbelt was created with idyllic, peaceful swimming holes like Twin Falls and Sculpture Falls.

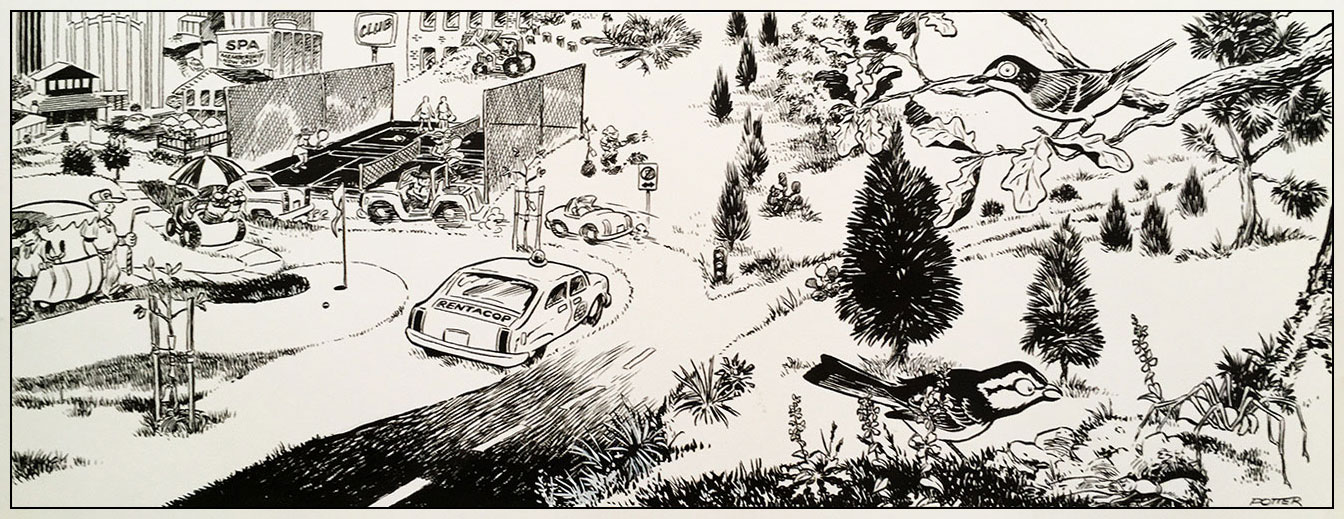

Austin growth cartoon, courtesy Doug Potter

These early environmental leaders, along with new allies, continued implementation of the vision. Advances included an environmental citizen’s board created in 1972 and even a new Waterway Ordinance in 1974. Citizens also voted down proposals to further extend sewer line infrastructure along Barton Creek guided by vocal politically savvy, newly emerging environmental groups like the Zilker Park Posse and the Save Barton Creek Association.

Also in the mid-1970s, a new scientifically-based focus on measurable water quality emerged. Environmental engineer Gus Fruh asserted that it was not enough for Barton Creek to have water quality standards to meet aesthetics, but that the City should request of the Texas Water Quality Board that Barton Creek meet “swimming standards.” SBCA members took Fruh’s ideas a step further and drafted the first ordinance specifically designed to protect Barton Creek, The Barton Creek Ordinance in 1980.

The Reckless

1980s

Then came the booming, wild and reckless 1980s. Near the beginning of the decade, the massive Barton Creek Mall opened just upstream from the Springs. As the decade progressed, money for land speculation and sprawling development flooded into town. Many exemptions were granted to the nascent environmental ordinances. Acres and acres of countryside were mowed down for new subdivisions and commercial development. These abuses were documented by Attorney Joe Riddell in the “Trail of Broken Promises,” a detailed chronicle of policy infractions, both by city government and private development. Even without the exemptions, multiple ordinance revisions in this time period ultimately fell short of providing adequate protections for Barton Creek, and signaled the need for something to be put in place. Meanwhile developers and environmentalists engaged in a lengthy, often frustrating, dialogue about a new watershed ordinance. The Comprehensive Watersheds Ordinance was finally passed in 1986. Once it passed, however, the City Council granted one exemption after another, with Mayor Frank Cooksey usually the only no vote.

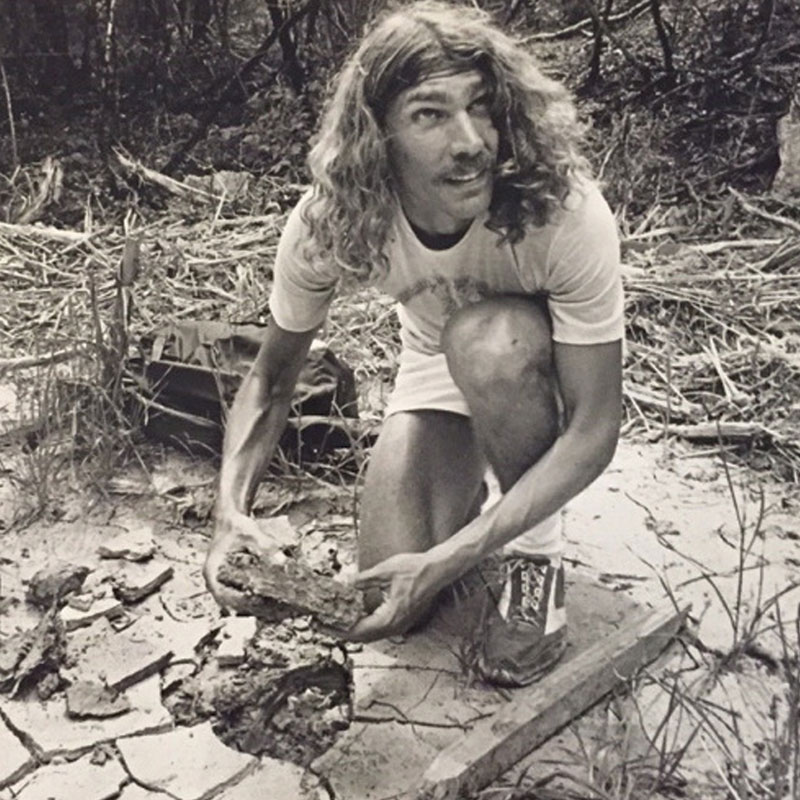

Photo courtesy: Austin American-Statesman

Lawyer Joe Riddell during his “Trail of Broken Promises” hike.

Finally in the mid-1980s the boom came crashing down. Development pressure on Barton Creek abated somewhat as Austin dug out from the collapse of the wild 1980s boom. Then in 1990 came the proposed Barton Creek Barton Creek Planned Unit Development (PUD), claimed by its developer as a way out of Austin’s bust. Thousands of citizens saw it differently and nothing so far in the environmental history of Austin had ignited public opposition as much as the proposed, massive, 4000-acre mixed-use development.

Barton Creek PUD Proposal Ultimately Leads to SOS Ordinance

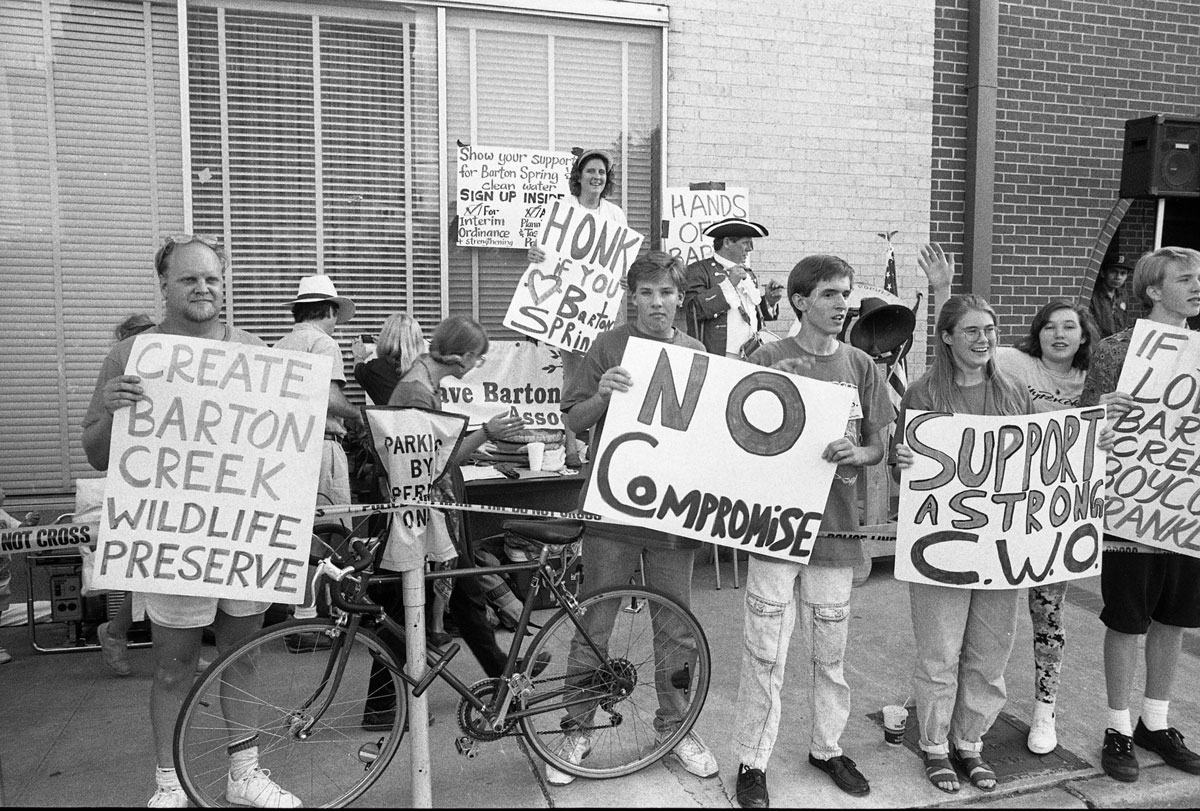

More than 900 people signed up to speak at the Council hearing on June 7, 1990 — the overwhelming majority of them opposed to the PUD. Hundreds demonstrated in front of City Hall. The chants of demonstrators and the sound of car horns honking in solidarity wafted into the Council Chamber every time someone opened the door.

Just before six the next morning, a Council originally thought to favor approving the PUD, voted unanimously to reject it. The would-be developers fought back in the courts and the state legislature, but never managed to build the exact development they wanted. They did succeed, however, in getting state laws passed that weakened Austin’s regulatory powers.

Photo by Alan Pogue

Austin citizens campaign for Barton Creek and stronger water quality ordinances in front of the Austin City Council Chambers, 1990.

Citizens determined that if a development like the Barton Creek PUD could come so close to realization, then current development restrictions were not strong enough. In 1991 and 1992 a recently formed group named the Save Our Springs Coalition, allying with older neighborhood and environmental groups like the Save Barton Creek Association, forced an election on a historically strong water quality protection ordinance for the Barton Springs Zone. On August 8, 1992, after an intense, hard fought campaign, the Save Our Springs Ordinance passed by a more than two-to-one margin.

The success of the citizen-driven Save Our Springs ordinance was a victory and turning point for Austin environmentalists and for Austin itself. Before the Save Our Spring movement, the City Council swayed back and forth between close majorities who favored environmental protections or majorities beholden to developers. Sometimes Council Members elected on environmental platforms crossed over to the other side. With the Save Our Springs movement, an ad hoc, grass roots campaign, environmentalists engaged in a direct confrontation with long-standing power brokers in Austin and won.

In the years after the SOS ordinance passed, a string of pro-environmental candidates were elected to the Austin City Council, first Jackie Goodman and Brigid Shea, then Beverly Griffith, and the author of this piece, Daryl Slusher. Eventually the movement to save the Springs was central to electing a Council where all seven members were strongly aligned with environmental causes, although the victories were also the result of forming and reforming multiracial alliances stretching across issues of social and economic equity, neighborhood protection, and environmental protection. Among other initiatives the Council began purchasing Water Quality Protection Lands (WQPL) stretching into Hays County. Currently the City owns about 28,000 acres of such lands.

Additionally, the environmental perspective began to be institutionalized into city government to a degree not seen before. Respect for the natural environment became a key element of Austin’s identity, a fundamental value. For example, Austin now has a nationally-renowned Watershed Protection Department full of people devoted to protecting Austin’s water. The city utilities, Austin Energy and Austin Water, are devoted to supporting environmental values of conservation and renewable energy. Although those efforts began in earlier years, but were solidified in the years after the SOS Ordinance passed.

The SOS Ordinance of course did not end the battle. Many developments were grandfathered under state law. Battles continued in the courts and at the legislature — and such battles continue today.

The Challenges of Today and Tomorrow

Today the Springs and Creek are still clean enough for swimming, although long time swimmers attest to a definite drop in water clarity. The survival of the Creek and Springs are testament to all the citizen efforts over the decades. Huge challenges, however, remain. For example, southwest Austin, over the Barton Springs Zone, has grown tremendously with multitudes of yards, roads, and parking lots from which pollutants can run off into the aquifer. Beyond that, roughly only one-third of the Barton Springs Zone lies within Austin’s jurisdiction.

For several decades now development has sprawled into these outlying areas. A fundamental issue is where the wastewater from all these developments will go. In Austin it goes into a centralized sewer, but in the outlying areas there are septic tanks and effluent irrigation, but, much worse are attempts to discharge treated wastewater into the creeks supplying the Springs. These battles are serious and ongoing.

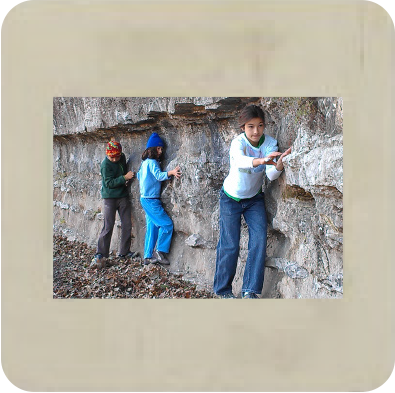

Still another problem plagues Barton Creek and the Barton Creek Greenbelt today. Barton Creek is being loved to death. Huge throngs pack swimming holes like Twin Falls any time the water flows and the weather is fair. The problem is that many do not have the respect for the creek that previous generations of Austinites did. Many carelessly discard trash. Hundreds of dogs run loose and defecate near the creek. Loud music disrupts the peaceful beauty and sounds of songbirds and gurgling water.

Many of the longtime defenders of the Creek and Springs remain involved and dedicated. They are aging, though. Ultimately the fate of the Creek and Springs will depend on whether new generations step forward to carry on the battle.